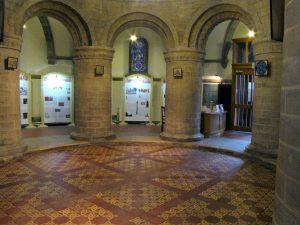

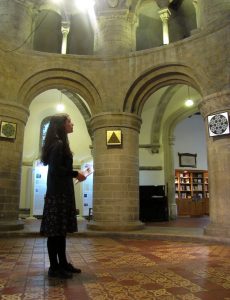

Solo Exhibition at the Round Church – Cambridge, UK – 30 Sept / 11 Oct 2013

A SITE SPECIFIC OR SITE RESPONSIVE APPROACH TO THE ROUND CHURCH? by Dr. Véronique Chance

‘Site-specific’ art refers to an artist’s intervention in a specific location, in the creation of an artwork that is integrated with its surroundings and that explores its relationship to its environment, whether indoors or out.

Also, known as ‘environmental art’, the term also applies to an installation or artwork that is made specifically for a particular gallery or public space, that is meant to become part of its locale, and in doing so restructures the viewer’s conceptual and perceptual experience through that intervention.

However, as artist and curator Gillian McIver has pointed out, the term ‘site-specific art’ [1] has also proved controversial, in that there has been some contention as to whether this ‘applies to work made specifically for a site’ (such as a commissioned public artwork or sculpture) or to ‘work made in response to an encounter with site’ [2].

Perhaps, the term is applicable to both? Whilst this may seem a moot point, there is she argues, a profound difference between the two types of work. In highlighting this difference she comes up with perhaps a more appropriate term for the latter, in what she calls ‘site-responsive’ art.

‘Site response in art’, she explains, ‘occurs when the artist is engaged in an investigation of the site as part of the process in making the work. The investigation will take into account geography, locality, topography, community (local, historical and global), history (local, private and national). These can be considered to be “open source” – open for anyone’s use and interpretation. This process has a direct relationship to the art works made, in terms of form, materials, concept etc. Of course, artists, like anyone else, respond to these “raw materials” [3] in individual ways.’

Macarena Rioseco’s paintings appear to belong to the latter category in the very particular relationships she draws out in both the architecture of the building and its religious setting, the term icon referring not only to the spatial geometry of a spiritual environment but also to historical devotional paintings. Here she has directly responded to her environment in her choice of materials, in the use of gold leaf and egg-tempera, those raw materials traditionally used for the execution of religious painted icons in the Byzantine era and in the geometric shapes she depicts. What these draw out are the larger philosophical questions inherent in the very terminology and paradoxical meaning of an icon, in that which is regarded on the one hand as a representative symbol of veneration, and on the other hand as infinite and unrepresentable. In doing so these small ornamental geometrical paintings draw viewers to not only look at the work itself, but to contemplate its existence (and their own), in both its immediate surroundings, the church, and also within its wider universal environment.

Dr. Véronique Chance

[1] Site specific art has been a subject of much critical debate in relation to contemporary art practice over recent years. Key texts include Erika Suderberg’s ‘Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art’, Miwon Kwon’s ‘One Place after Another : Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity’ and Clare Docherty’s ‘Situation’ (Documents of Contemporary Art).

[2] McIver, Gillian ‘Art/Site/Context’, from the author produced critical website www.sitespecificart.org

[3] Ibid.

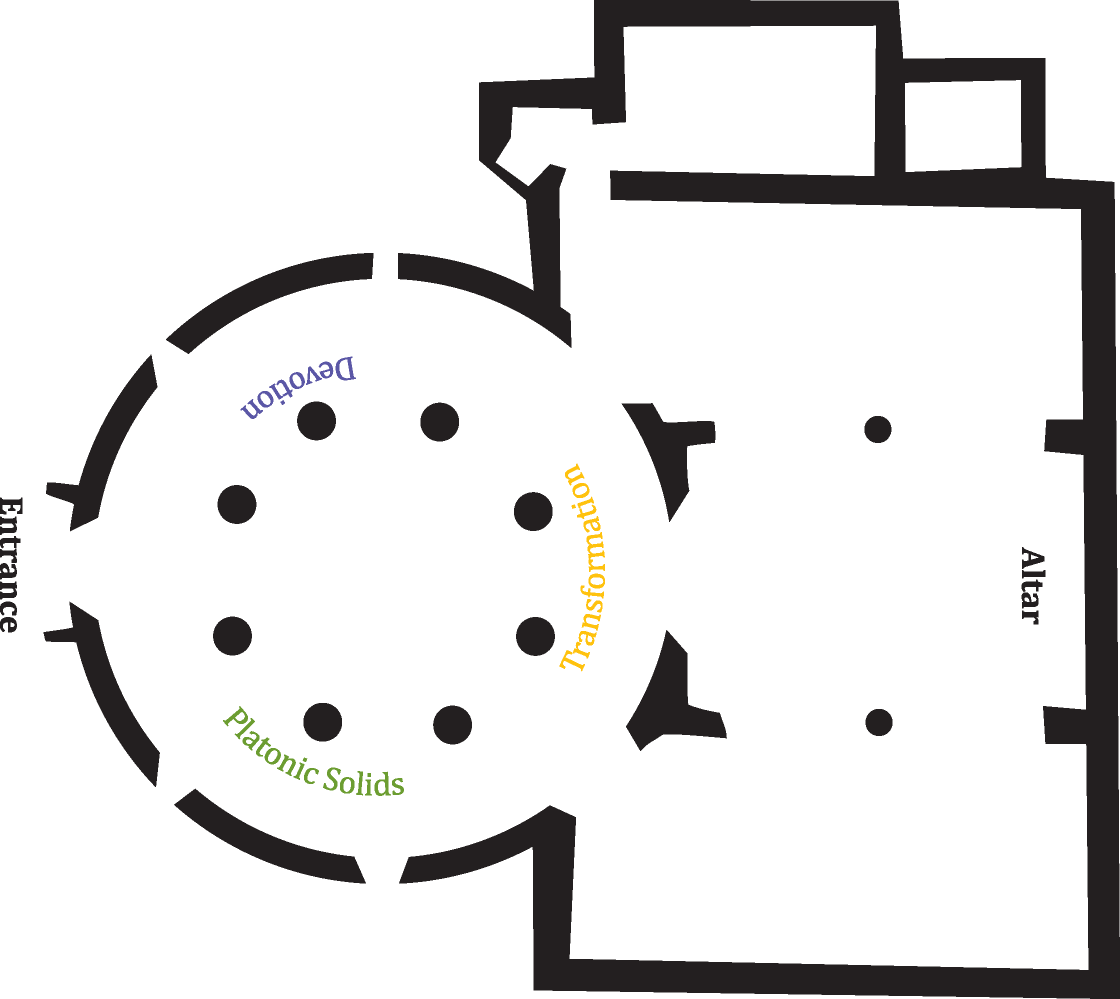

Round Church Plan

Links to Works: Devotion – Transformation – Platonic Solids

‘The icon is a sign, not a representation: its figurative elements are conventional significations rather that portraits of an earthly being, and its space is a cosmic, two dimensional, unchanging gold, a sign for an in nite spiritual reality that cannot be pictured’. (Gooding, Mel. 2001. Abstract Art: Movements in Modern Art)

Fractal Geometry was formalised in the late 70s by the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot and came to extend the classical framework of Euclidean geometry that had been dominant for centuries in Western philosophical and scientific thinking. According to Mandelbrot, a frac- tal is “a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be split into parts, each of which is (at least approximately) a reduced-size copy of the whole”. Presenting a dynamic interrelationship between the parts and the whole, in a fractal shape, every unit is a whole and a part at the same time, and as a consequence of this iteration, fractals are theoretically eternal. Interestingly, while Fractals were introduced to the scientific community only recently, their presence is apparent in numerous artistic and religious expressions since ancient times.

As an interweaving between notions belonging to science and religion this project was constructed and guided by concepts that can be found on Leonardo Da Vinci’s writings and Plato’s Timaeus. Plato’s idea that “the universe is in the form of a sphere” allows us to establish a direct relationship with the site. Being the sphere and the circle continuous shapes, that is to say, having no beginning or end, in this sense, they can symbolize unity, wholeness and infinity. Also as described by the Greek philosopher: “having its extremes in every direction equidistant from the centre, the most perfect and the most like itself of all figures”, therefore, “a body entire and perfect, and formed out of perfect bodies.”

In the case of Da Vinci’s writings, ideas were exposed on how the uni- verse could act as a source of philosophical knowledge. However, he added, “in order to understand it, one must first study its language and letters. It is written in the language of mathematics and its letters are triangles, circumferences and other geometric figures, without a knowledge of which it is impossible to understand a single word.”

In Fractals: Icons, the rotunda of the Round Church appears as a perfect wholeness, container of eight Icon paintings depicting fragmented geometric shapes. Altogether, with these paintings the intention is to convey ideas like the one presented by Fractals that states that we are all wholes but, at the same time, we are also parts of a bigger one, just, at different scales of magnification.